When I started this blog, I knew it had to have a concrete purpose. The last thing I wanted was a spot on the internet where I would fervently air my opinions on whatever happened to cross my mind that day and expect people to care. I am not mocking that format. I know some people do it very well, and some need that outlet. The interactive diary thing is certainly the medium of our time. However, I am an artist who has three things he should be drawing right now. If my creative energies need venting, there are plenty of much more productive ways for me to be doing that than diary blogging. And, as all of you are probably well aware at this point, I tend to ramble on at the mouth. I’m nearly as deeply invested in music and movies as I am in comics. The last thing I need is to feel like strangers await my stray thoughts on those as well.

So every bit of this blog has just been an extension of my physical class. I haven’t even used it to make pertinent announcements about my own art or doings aside from last week’s alert (at Sean T. Collins insistence) that I was attending New York Comic Con. I like that about this site. I feel it separates it, gives it a real sense of purpose, and keeps me more professional.

BUT…

(Sorry Chris Ware.)

…Ima gonna ramble about my experience of New York Comic Con.

Why am I breaking my personal rule? There’s really only one reason:

I have alluded frequently to my trip to Japan on this blog. It occured in the summer of 1999, using money from multiple grants and fellowships. Its express purpose, seriously, was for me to study the comic culture in Japan. Natsume Fusanosuke, manga-ka, critic, and grandson of Japan’s most famous novelist, set up everything for me based on one impassioned letter I sent him. He got me a place to stay, interviews with Japan’s hottest manga-ka (comic creators), assistantships with some, invitations to Studio Ghibli and television events, and tickets to museum shows across the country. I could have written a book when I returned about all my experiences and new understandings.

But I was a cocky twenty-year-old with no experience with interviews and a weak grasp of Japanese. The first interview I did, with an editor from an old comic mag, I recorded on microcassette. The next, with the creator of the marvelous Z-Chan, I started to record, but I could see it made Iguchi San nervous, so I shut it off. We had a mind-blowing talk. I do remember that. Even my translator felt like it was one of those nights in which you see everything differently afterward. I have no idea what was said. Music. Life. Stray words. This became the norm for my interviews. I believed, foolishly, that as an artist, these words were for me, and that I would retain whatever nuggets of wisdom were truly inspiring. Or that their lessons would find their way into my art in some subliminal way; leaching in, or some such nonsense. The only concrete thing I have to show for all the time wonderful people spent with me is a handful of tapes in which, on various occasions when we weren’t watching movies or laughing, Takekuma Kentarō, writer of Even a Monkey Can Draw Manga, explained to me the history of Japanese comics. These are untranslated, as I thought I’d get more meat by letting Takekuma go in his native tongue. His English was better than my Japanese, much better — which is still to say largely incomprehensible. I’ve attempted to listen to these several times, realized I have forgotten whatever Japanese I once knew, and returned them to their dusty box. I am sure they are brilliant, and probably hilarious.

I consider all of this lost knowledge. I feel I betrayed the time people spent with me. I regret this loss more than any sketchbook of mine that has found its way into the ether. I can only hope that one day, each person who spent time with me can find a panel or a page I drew, nudge the person next to them and say, “I taught him that.” And I’m sure they’ll be right.

So with that absurdly lengthy introduction, (I told you there’d be rambling) I come to the responsibility at hand. Last weekend, I used the New York Comic Con to track down everyone in attendance whose work I respect and admire. I then proceeded to pick their brains about choices that seem central to their work. I was a thief, out to steal as many techniques and ways of thinking about comics that I could. Because all of this was very much done informally, I am using this space to record what I learned before it fades with the rest. This is just my personal notepad of two days in New York (mostly) at a convention for a field I love. The insights I record here will likely find their ways in a more finished form into proper posts. I can guarantee there is stuff to learn in what follows, but it will have all the organization of my walk through the bustling crowds of a somewhat randomly laid out convention hall. This is Poldy Bloom does Comic Con. You’ve been warned.

DAY ONE: Friday

The Con did not start until one and former college roomie Sean T. Collins had to “work” as a “professional writer” until three, so I took advantage of being back in the greatest city in America. I lived here for a year after college, so of course I had to visit one of my favorite old haunts: the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Seriously, I am culture STARVED in Northern Maine. I did not go get a Papaya Joe’s hotdog. I have no money for fashionable clothes from SoHo. I did not run to a deli in Queens. CBGB’s was dead (albeit unofficially) in 2001. I MISS MY MUSEUMS! When I lived here, I worked for Bloomberg and, thanks to his philanthropy, I could attend any museum for free. And I did. Every weekend. I mean, technically, nearly anyone can do this as most museum fees are suggested donations, but I could do it guilt free. A billionaire (and future mayor) had paid my ticket.

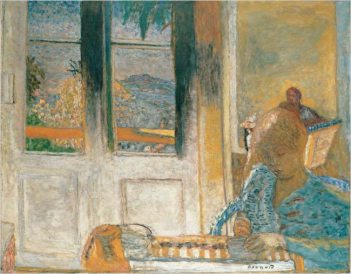

Now, I love the Guggenheim, and I really wanted to see MoMA’s new space, but the Met had a Bonnard show. Done deal. I honestly wanted to come to New York for this as much as Comic Con. For years I’ve read the Sunday Times and lamented all the shows that were passing me by. Kirby at the Jewish museum. Ian McKellan in King Lear. I’d pretend I was actually working out ways to see them. The clippings would hang on our bedroom wall. But Bonnard would have really killed me to miss. I knew it could be life-changing.

I was not wrong.

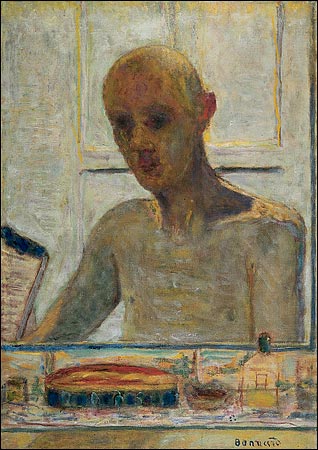

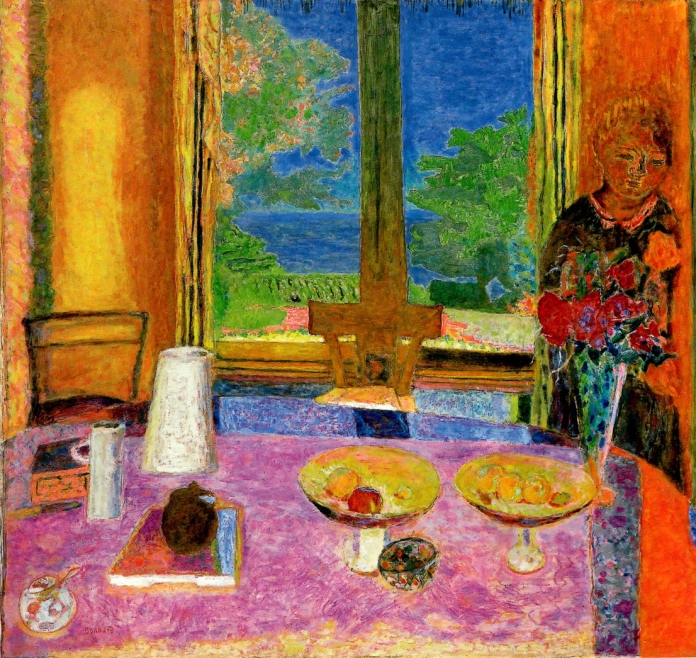

art: Pierre Bonnard title: Before Dinner

art: Pierre Bonnard title: Portrait of the Artist in the Bathroom Mirror

All the colors of these famous ones are completely different in reality. You would not believe the strength of the dash of pure cadmium red on his ear in the self portrait above, all but imperceptible here. He’s really glowing with color. Also, the handling of the items in the flat space of the foreground is appropriately and boldly slapdash.

In person on this one, you can see that the handling of the paint is completely different in the section that is out the window. That stuff is watery, “tube colors”, whereas the interior is covered with mixed impasto. The woman, his wife Marthe, is also much more hidden. The effect is similar to what happens in the center with the frame of the window and the back of the chair: they function, compositionally, as one.

As pretentious as this sounds, I’m actually a little surprised there was not more crossover between the crowd here and at the Con.

The crowd at the Met, in reality, seemed impressed but largely ignorant of the true appeal of Bonnard. I had to suffer through loud conversations of the rich regarding whether or not they should arrange their dinette as was shown in a particular interior. They would have been better served by discussing the arrangement of the rectangular blocks of color. Bonnard was painting from memory. Whether that does or does not remind one of an actual wineglass or pitcher of juice is completely irrelevant. But he, Matisse, Gauguin and a few others mastefully pushed the limits of “representational” objects serving dual roles as forms within the imagined space of the painting while more importantly behaving as compositional anchors: pure shape or color for the sake of the design.

I think comics fans would get that.

art: John Porcellino book: King Cat Comics and Stories publisher: Drawn & Quarterly © John Porcellino

art: Chris Ware book: Quimby the Mouse publisher: Fantagraphics © F. Chris Ware

art: Ron Rege, Jr. book: Yeast Hoist publisher: Drawn & Quarterly © Ron Rege, Jr.

The “high” art world famously took this concept a bit too far. I, personally, am sad to see that form has become almost completely divorced from representation in a real space — unless for the sake of some sort of irony. But I believe comics artists like those above have taken that torch from the painters of the late 19th/early 20th century and run with it. There’s a democracy of line and handling that leads to very interesting experiences of space. The image can be viewed as a flat, two-dimensional balancing act of formal elements, but it can also be appreciated as an abstraction of three-dimension space that can be wandered through.

Bonnard used this dichotomy to amazing effect. There is still so much to be learned from his compositions. His favorite trick was to subjugate absolutely everything within the picture to the demands of the design, which led to figures appearing “hidden.” This result really just stems from the total universality is his handling of forms. Aside from the self-portrait above, people are treated by Bonnard the way a great scientist like Darwin or Copernicus would have done: We are given no special treatment or place in the universe. If a vase only gets three tones and 37 brush strokes, so does the woman in the foreground. The effect is similar to Kevin Shields treatment of the human voice throughout My Bloody Valentine’s amazing album Loveless. The vocals are not “buried”; they just receive the same mixing and processing as the guitars or any other instrument. Go back and look at the first painting I displayed here. Perhaps you failed to notice the figure against the wall to the left. No? Well, how about the one on the far right? I would argue that this rounded form is the hair of another lady, with a large-nose and cartoony face in profile beneath it. Why should these figures “jump out” and distract us from all the other beauty this image offers?

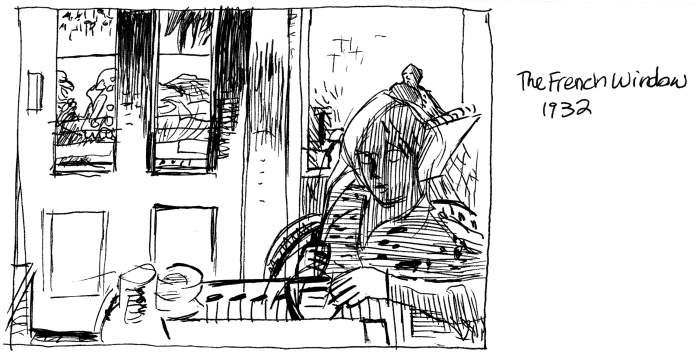

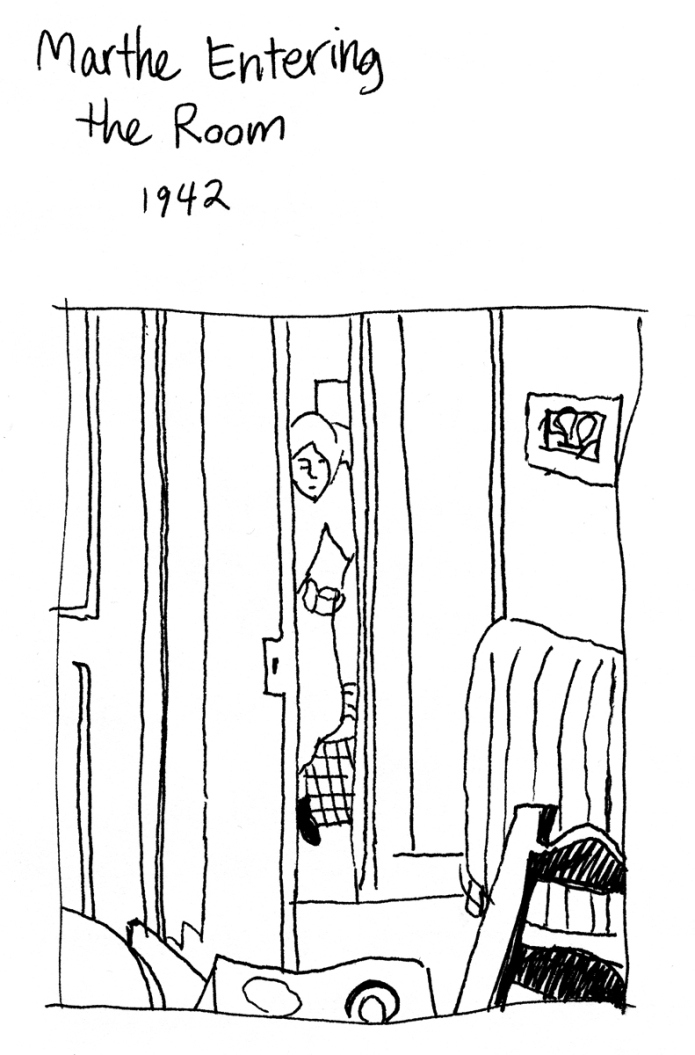

Below are some sketches I did that hopefully tie all these considerations together. Thumbnails of the original paintings precede them.

art: Pierre Bonnard title: The French Window

The reproduction above makes it appear as though it is abundantly clear where these figures are. I assure you, it is not. And that is the true fascination of this painting. A good third of it is nearly negative space — just the inner frames of a white door. Through the windows on the door we get an overload of information, islands and water and trees are crammed into these tiny slits. In one sense, these rectangles are merely pattern. Viewed another way, you shoot deep into that outdoor space because the emptiness of the doors handling contrasted with the clutter of the exterior mimics our eyes own focus shifts. The right side of the painting, in person, reads mostly as darkness, and is thus the last area to be explored. We have the wonderful horizontal rectangle composed of vertical stripes that mimics a table in the foreground and leads us into the shot. It is only by following that to the items it supports that we make out the darkened lady in the foreground. The splotches of the pattern of her dress are no different from the impressionistic trees and bushes out her window. Her face in nearly entirely in shadow aside from a crescent of hair on top. This rounded shape connects with two further semi-circles, apparently receding deeper into space. Indeed, because of the negative space of the back wall, space on the right of the picture seems impossibly far deeper than the exterior we are shown at the left. Deep in that back corner of the painting and room, the only item that can be clearly discerned is the corner of a table. By a leap of logic we assume perhaps a figure is sitting next to it. I swear, it was only after I finished drawing all this and I read the description (usually garbage, here helpful) that I realized what I had drawn. The three semi-circles were all indeed heads. The first: the discernible woman in the foreground. The second: the back of her head. The third: the artist himself! Behind the lady is a mirror! That strangely cantilevered rectangle with the coils atop is the artist’s sketchpad! He is painting the scene within the self-same shot. But ignoring all that, what is really going on is a beautiful balancing act of large rectangles. One might even call them panels.

Take your hand and cover up the lower half of my sketch. It’s just a series of verticals! Here Bonnard has pulled off the impossible. One should not be able to put the center of interest square in the center of the image! Especially when there aren’t even horizontal or diagonals to bounce the eye around to other spots. The design rule is of thirds: divide the page in three and place the subject at the one-third or two-third line. Dead center? Not for a fine artist! And look at the subtle insets of the door at the left and the radiator on the right. Taken together these basically make a horizontal intersecting perpendicularly right across the center of the image again! We’ve basically got Bonnard’s wife in a crosshairs! It’s a composition like a seven-year-old might do: fold the page in half twice and draw the girl you like smack dab in the middle. THIS SHOULD NOT WORK! But, aha! look at the color version above. Marthe is barely visible in that tiny central slice. The subject is the door! And it’s right where it should be: one-third. And there’s a nice heavy, dark chair to balance it in the right extreme foreground. Our human protagonist is literally squeezed into a few inches in the middle, her presence the only thing throwing off the perfect minimalistic harmony of the verticals. Everything in the painting suggests this person dead center is intruding on a space that was complete without her. The grid of the tiled floor is the only area that is handled with the detail of a fine brush, and it echoes the perfection of cold geometry. She’s covering that up, too.

The show was amazing. There were so many other works there that deserved sketches and ponderous analysis as well. I only wish there had been a few of his truly famous bathrooms as well, but I guess those must have fallen outside the date range they had established. Anyone interested in color, pattern, form, design and layout (and by that I am basically saying anyone interested in comics art), owes it to herself to catch it while it lasts.

I dashed around some other wings before leaving to grab a cab to the show. As a parting gift, I present here some other comparisons that occured to me given the confluence of thoughts for the day.

MORE FUN WITH HIGH/LOW FORMAL CONNECTIONS!

art: Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri) title: Samson Captured by the Philistines

art: Mike Allred color: Laura Allred book: X-Statix publisher: Marvel Comics Group © Marvel Comics Group

GUERCINO = MIKE ALLRED

Blank space

art: Max Beckmann title: Beginning

MAX BECKMANN = DAVID MAZZUCCHELLI

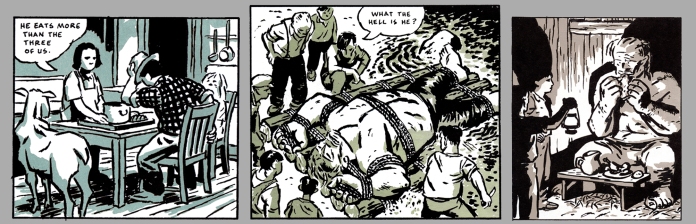

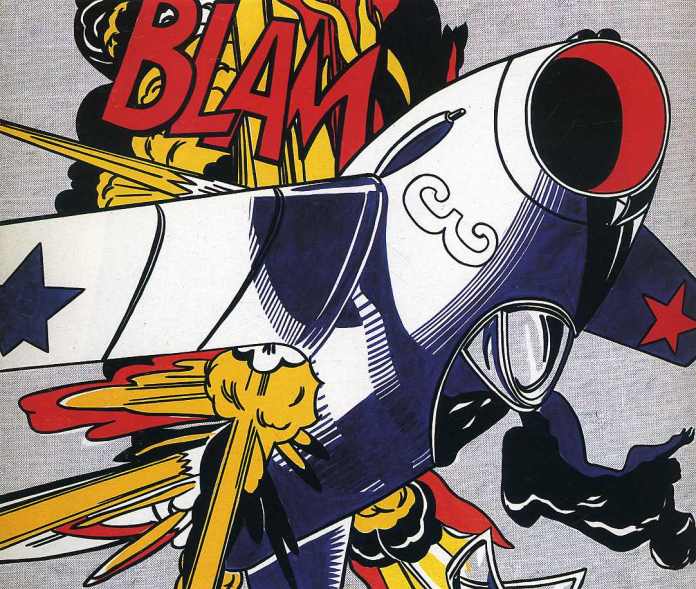

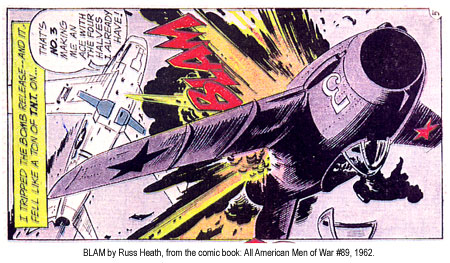

ROY LICHTENSTEIN = RUSS HEATH

Hey — wait a minute…

art: Josiah Leighton after Pierre Bonnard

art: Josiah Leighton after Pierre Bonnard