John Crowley, eminent but under-read novelist, used to toss off koan-like questions on a daily basis in his Craft of Fiction course that would cause me to completely reevaluate what I thought I knew about storytelling. One day it was “All stories have narrators. Even if a narrator is unnamed, unmentioned or omniscient, we have to ask: Who is he or she? What does he know and care about, and what is he ignorant of? Who is he telling this story to, and why?” I mean, clearly David Copperfield has a distinct authorial perspective, but what about “It was a dark and stormy night” and its ilk? The notion that a novel which eschews first-person narration and does its level best to just relay a plot must necessarily have a specific perspective which may or may not mirror that of its creator was mind-blowing. But he was right.

On my ride to work years ago I used to listen to the Great Courses lectures from The Teaching Company. One brilliantly explained relativity and quantum physics without math. Even much of a dumbed-down course like that was over my head, but the upshot of Einstein’s overhaul of Newtonian physics was not “No, that isn’t right,” but rather “Yes, but relative to what?” Two people can play tennis on a moving cruise ship just as they can on a static court (attached to a moving planet which is cruising around the sun in a galaxy which is hurtling away from a central point) because if the people and the ball and the court are all moving at the same rate — well, they may as well be still, right? Even when immobile they are moving relative to the water beneath them, but not relative to each other. So in contemporary physics, we must always consider our perspective. Whose in charge? Rationally, it seems like if I jump up in a moving bus I will land further back. I seems like I could save my life in a plummeting elevator with a well timed jump. But I can’t. Because Einstein was right too.

And filmmakers have unearthed some fascinating insights on how our brain pieces disparate images into a narrative. Despite the illusion of reality created by stacking frames on top of one another in our visual field in rapid succession, despite the twists and turns of the action in the imagined space of the narrative, our brains still retain an after image of the literal space of the camera’s frame. Within a scene of dialog, filmmakers have found that you must stretch a string (or, like Einstein, do a thought experiment and save yourself some string) from one actor’s eyes to the other’s, set up your camera and equipment on one side of that string, and never cross it! The string mimics the actors’ perspectives of one another, and then we — meaning the camera, meaning the narrator — must choose a perspective on the two of them. Perhaps we choose one side of the string which ensure Person A is always on the right of the shot and Person B is always on the left. Or perhaps we choose the other side which will completely reverse their orientations. It matters not which side we take. But once the choice is made, we have a specific point of view. And to cross that line of sight mid-scene is as jarring to the audience as a Horatio Alger story suddenly launching into an attack on the heartlessness of capitalism. Our brain is able to follow the narrator because we have a consistent perspective. Ah, Person A is on the right: God is in Heaven, all’s right with the world. No matter how the characters shift and jump and gesticulate, my brain maintains a sense of spatial order. This is known as the 180 Degree Rule.

Well, sequential art is also beholden to the rules of space, but it is a literal space, not a cognitive one with a time component. Filmic rules involve the act of remembering. The 180 Degree Rule establishes and adheres to a pattern. But the comic book page is a single piece of artwork as well as a collection of narratively linked images. I as a reader can travel backward and forward and sideways in time just by sliding my eyes around the page. I would love to here that Teaching Company professor’s discussion of this model of space-time! Because all of these individual images are juxtaposed, not merely the ones in sequence, a consistent narrator’s perspective is vital. We must understand who is in charge. We must have a point of view: a set of eyes, a lens through which we are viewing these events (i.e., panels). Now, to limit our discussion at present to just the immediate concern of this broad topic, let it suffice to say that consistency in point of view should not be reduced to Cloverfield-style first person shooter camerawork. Comix is not film. There is no equipment to keep on one side of a line. And respecting the sight line in an imaginary brain-space created by stacked memories is not nearly as pressing a concern as respecting the actual lines simultaneously visible on the physical page and the interplay of sight lines contained therein. In brief — and this topic is explored at greater length in numerous posts throughout this blog — the 180 Degree Rule does not apply to comix. We must keep our readers comfortable by leading them logically through the page with sight lines and head angles, bouncing them off the edges of our tiers into the far left panels below, and this ricocheting movement practically necessitates breaking this filmic rule. Nevertheless, the larger point remains: readers must be aware of the perspective through which they are viewing the story. The question “Relative to what, or relative to whom?” should never need to be asked, because accomplished artists should lead us effortlessly through the ever-shifting scenes.

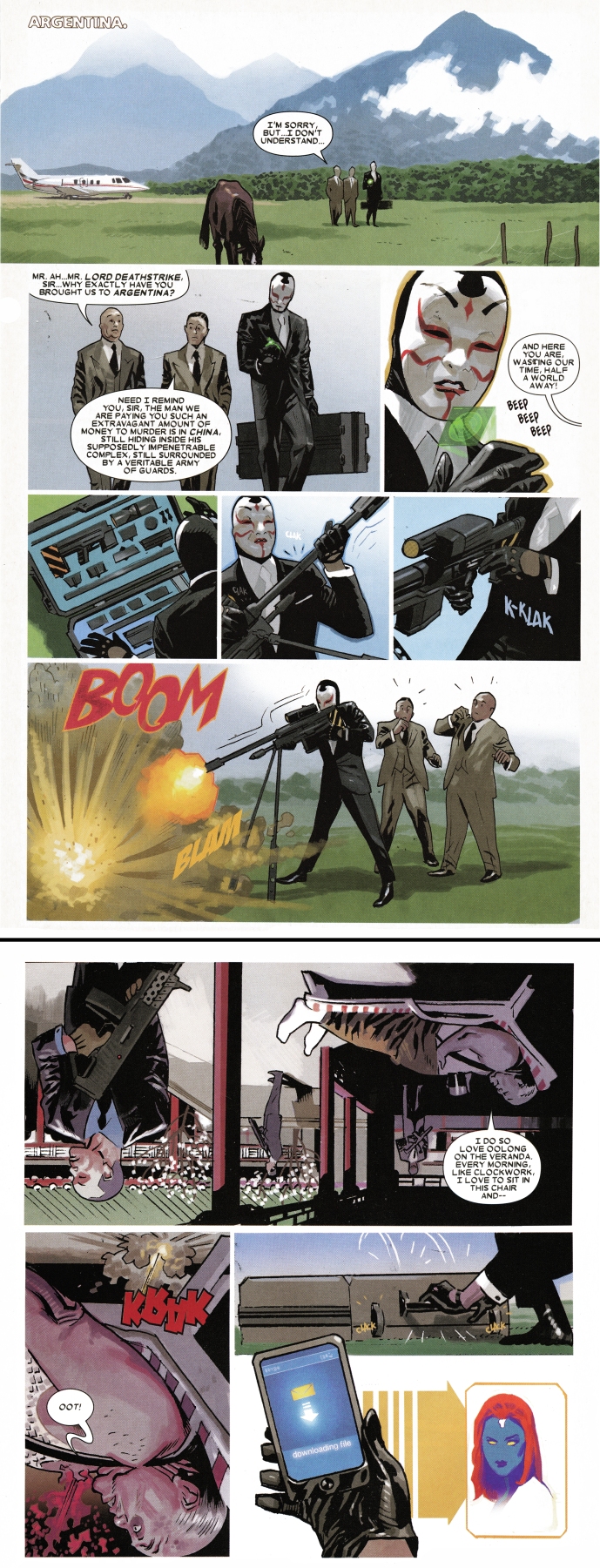

Now, Daniel Acuña is an accomplished artist. In fact, in a period of near total withdrawal from comic collecting activity, he forced me to track down his every book. Eurocomics meets X-Men? Photoshop brushes so forcefully undisguised, and to such beautiful effect, that it makes us all want to give up on coloring with Photoshop? Yes, please. And at some point I may begin a Category on this blog called “Perfect Pamphlets” to highlight the Art that sometimes emerges for 22 pages in a row in the seemingly throwaway monthly medium, and if I do Wolverine Volume one million Issue Number 9 will make the list. This floppy comic book is an action movie’s worth of chase scene combat told in four perfectly selected panels per page. Jason Aaron’s story is even audaciously and amusingly absurd as well. Wolverine #9 is something akin to Crank 2 in comic book form. There’s a secret, shadowy cabal with a farmer in overalls sitting at it. There’s a one-eyed John Waters/Vincent Price auctioning off the newly murdered Mystique’s dead body to ninjas. And there’s the below:

Now don’t get me wrong: I love it. This is so preposterously dumb. This is the “dig your way to China” comment played straight in the ultimate bad-ass assassin scene. But tell the truth: for a split second between pages one and two you had to have the joke explained. And timing is everything in comedy. So let’s try this one more time with a slight adjustment and see if we can nail that punchline:

Our scene is from the gorgeously designed Lord Deathstrike’s perspective. Relative to him, China is, as a third-grader imagines it, upside down. If quantum physics has taught us anything it must be that sometimes the seemingly strangest solution turns out to be the simplest and most apt. Now we snap back to Deathstrike’s side of the planet the second his suitcase snaps closed, and we’re off with him to his next target.